The word ‘asset’ – or ‘asset management’ – is now used so often that we could be forgiven for forgetting what it means. The Oxford English Dictionary says that an asset is ‘a thing of use or value’, and for most media businesses their content is their lifeblood. So it makes sense to treat content as a critical asset, and ensure that it’s safeguarded and available as necessary.

The value of an asset may be in different forms. Producers of movies or television programmes will see the finished work as an asset to be sold to broadcasters and other outlets around the world. When discussing asset management, people often talk about monetising content in the future, and this is certainly important.

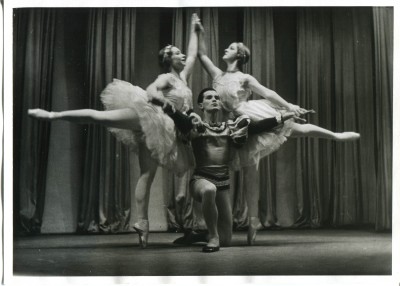

But the value can also be realised in a different way. At BBC Studios and Post Production Digital Media Services we recently conserved the archive content of renowned dance company Rambert by digitising it. Their collection – on VHS tapes – is the company’s cultural history. If they wanted to revive one of their ballets, the choreography was only available as a video recording, so they needed continuing access to their archive.

BBC Studios and Post Production’s award-winning Digital Media Services team is digitising 650 hours of archive content for Rambert, the world renowned national company for contemporary dance.

With VHS players rapidly dying out, it was becoming harder for the company to watch the recordings. Rambert’s motivation to digitise its archive was, then, not to monetise it but to conserve it for future generations of dancers and choreographers. They’ve also made it accessible, free of charge, to the public, so it serves to improve public awareness and extend their marketing reach.

So it is not just broadcasters and production companies who have audio-visual assets. Universities, charities and cultural organisations have collections which represent an important part of their heritage, which must be sustained.

The critical point to remember is that, if an archive is on tape, you have to address this issue now. Every time a tape is played it is being worn, reducing its quality the next time it is played: tape has a very finite life. And, of course, it’s increasingly difficult to find players for the many tape formats we’ve seen over the 60 year life of video recording.

The solution is digitisation, but on its own that is not enough. It may seem simple to go to the local computer store, buy a couple of USB disk drives, write the content to them and put them on the shelf. But that’s not a good long-term idea for media. That sort of disk drive is designed to last no more than a few years in reasonably constant use. Leaving them on the shelf means they’ll almost certainly fail the first time you go back to them, so your media assets still have no protection.

In the long term files and formats need periodic migration to remain accessible. Just as a tape format requires a specific deck to play it, disk and file formats need compatible file systems and software to remain playable.

Protection

So the first consideration must be to protect the assets into the future. That means making copies and then continually checking the integrity of the data. Whether the archive is stored on spinning disks or data tape, and whatever form the archive storage takes, you need to be continually aware that the data is securely stored and can be retrieved when required.

Because of this need for continual checking, unless your archive is so vast you can sustain your own dedicated team it makes sense to hand the task to an organisation that has the resources to continually monitor the integrity of your data. They’ll operate securely redundant storage, usually in multiple locations, and will have archive management software which is continually running checksum calculations across the sites on the data to spot errors and rewrite files before they become a problem.

Kevin worked with BBC Studios and Post Production’s Digital Media Services to build their state of the art facility in South Ruislip, which opened in 2013.

At BBC Studios and Post Production Digital Media Services we’ve built a bespoke facility in South Ruislip to handle content of any type and size. We can offer a complete solution or provide specialist services to company archives. Our mandate is to offer film and tape digitisation, migration, hosting and archiving. This uses the latest technology to provide highly secure but compact and cost-effective storage, across disk and data tapes, coupled with powerful data integrity software to identify the inevitable data loss before it becomes critical and can’t be recovered.

Visibility

The archive may exist to raise revenues or protect a cultural heritage; it may be open to all or just a small group of researchers. Whatever the requirement, the content will need to be accessed by some people, so it is vital that the archive is visible.

That means two things. First, there must be good metadata to help the researcher find the right content quickly and accurately. A search which brings up hundreds of possibilities is as useless as one which delivers nothing. Each archive will be different and therefore have a different metadata schema. If you use an archive specialist they’ll be happy to discuss the structure of your database.

Normally the database will be linked to a browse server, so you can view the selected material, and maybe even perform simple functions like clipping or assembly editing, without recovering the full resolution files from the archive.

The viewing proxy copy, and good metadata, are important so that future users can find, reuse and repurpose an asset. An archive cannot be monetised if no-one can efficiently find anything in it.

For some archives only a very small closed user group should be allowed to access the content; for others it could be opened up to a larger group or even potentially everybody. It all depends on the nature of the content and the way you hope to realise its value. But the big difference to the tape and indeed the simple files on disk approach is that the full resolution master file is always copied when needed, which avoids loss or damage during use. An asset is most vulnerable precisely at the time it is most valuable!

Restoration

BBC Studios and Post Production’s Digital Media Services team won the FOCAL International Award for the restoration of two landmark David Attenborough nature documentary series, ‘Life on Earth’ and ‘Trials of Life’.

Another central question is how much restoration should be carried out before committing content to a managed archive.

Restoration tools – automatic and manual – are already extremely capable. We recently won a FOCAL Award for remastering two landmark Sir David Attenborough nature documentary series, Life on Earth (1979) and Trials of Life (1990), and although the 16mm film was more than 20 years old, it now looks like it was shot yesterday.

16mm film, well restored, is a perfect match for high definition television. That means that if you perform a full restoration today, you can then regard the archive as the definitive version for the future.

But technology continues to advance, and 35mm or other formats may benefit from future developments. So for some of your archive you may decide to capture and preserve the best detail you can today and apply the best restoration tools at the time of re-use.

At our dedicated facility we’ve implemented a range of workflows including an Academy Color Encoding System (ACES) platform which can be used, if required, as a means of capturing raw data today for preservation, ready for future restoration work as technology allows and the market demands.

Making the content immediately available to its target market of users is a good way to determine priorities for restoration. Market demand for content will demonstrate what is popular, and user comments on quality will underline what work is required. Together they will help you set up a targeted programme of work. For some organisations, unlocking the value of the archive content is sufficient to pay for the cost of the archive.

Preservation

In conclusion, there are a lot of organisations who have audio-visual material which should be preserved because it will have value, in some way, in the future. Along with the obvious broadcasters and production companies, these organisations range from sports federations to charities (we have recently undertaken the management of Oxfam’s archive, for instance).

The chances are that the content will exist across a broad range of formats. This will include film, and at BBC Studios and Post Production Digital Media Services we maintain one of the last functional Rank Cintel Mk III telecines with gates for obscure gauges like 9.5mm, as well as the regular 8, 16 and 35mm.

But much more pressing is video and audio tape, which is degrading faster than film and is significantly damaged by the wear of each play. Again, we have a remarkable collection of machines to get the best out of those tapes, and a team of engineers who can service our VTRs and customise the hardware to create bespoke preservation workflows.

The critical message, though, is that you cannot put off this task: preservation has to be considered now or the content will degenerate and may be lost forever.

For more information please visit www.bbcstudiosandpostproduction.com

(As well as being a freelance colorist and ICA instructor, Kevin is Lead Technologist at BBC Studios and Post Production Digital Media Services)